Using artificial intelligence to refine laser interferometers for gravitational waves: this is the goal of the research project “Deep Loop Shaping for Gravitational-wave Detection,” which has received funding of €1.836 million under the third call of the Italian Science Fund (FIS 3), financed by the Ministry of Universities and Research (MUR). The project will be coordinated by Jan Harms, professor at the Gran Sasso Science Institute (GSSI) in L’Aquila and deeply involved in the Einstein Telescope scientific collaboration, where he is co-coordinator of the Instrument Science Board (ISB), responsible for defining the technical design of the future gravitational wave detector.

The FIS 3 call aims to promote the development of fundamental research at the European level, following the model of the European Research Council (ERC), by funding projects with high scientific content for a total of €475 million. These projects are led by emerging researchers (starting grants), mid-career researchers (consolidator grants), and established researchers (advanced grants).

The project coordinated by Harms is part of the advanced grants category and will run for five years. Its goal is to strengthen a line of research launched several years ago, stemming from a collaboration between GSSI, Caltech (California Institute of Technology) in Pasadena, and Google DeepMind, which already led to a publication in the journal Science last September.

We spoke with Jan Harms about the challenges of the project, whose main focus is on gravitational wave interferometers currently in operation (in particular Virgo, located in Cascina near Pisa), while also paying close attention to next-generation detectors such as the Einstein Telescope.

Jan Harms

What is the scientific starting point of the project?

One of the main challenges in gravitational wave detectors is controlling the many types of noise that can hinder the ability to observe a signal. Some are unavoidable: for example, noise produced by ocean waves generates micro-movements of the Earth everywhere, especially at low frequencies (around 1 hertz), even far from coastlines. It is therefore necessary to continuously compensate for these movements in order to keep the suspended mirrors of the detectors stable. The problem is that these same control actions, which are necessary to stabilize the system, themselves introduce another type of noise, known as “control noise”. Already in current detectors, such as those of LIGO in the United States, it has been clearly observed that at low frequencies these noises become dominant and limit the sensitivity of the detector.

How can artificial intelligence (AI), and in particular the technique you have developed, help solve the problem?

The idea is to use a nonlinear approach based on neural networks. These methods allow detector signals to be transformed in a much more sophisticated way than classical control techniques. We call this approach Deep Loop Shaping, a technique based on so-called “reinforcement learning”, that is, a type of machine learning in which the algorithm learns to generate optimal control signals through trial and error. Specifically, we have created a digital twin, namely a very realistic simulation of part of the detector, into which we incorporate noise models, environmental dynamics, and time-dependent noise variations. We train the AI on this simulation and then transfer it to the real system, that is, the actual detector.

How have the tests carried out so far gone?

After developing the algorithm and implementing it in a prototype at Caltech, with crucial support from colleagues at Google DeepMind, we transferred the system directly to the LIGO detector in Livingston. In less than a year of testing, we managed to reduce a certain control noise by a factor between 30 and 100 in the relevant frequency band. Of course, this does not mean that the overall sensitivity of LIGO improved by the same factor, since we did not apply the algorithm to all control noises, but it was the first real demonstration of the effectiveness of this approach.

What objectives have you set with the new project funded by the FIS call?

The main goal is to bring this technology to the Virgo experiment, in order to increase the detector’s sensitivity by applying our technique to multiple control noises. But there is another important open problem we want to focus on: in general, noise is not constant, but varies significantly between different seasons, and even simply between day and night. It is therefore necessary to develop algorithms that can adapt to changes in noise. To do this, we will need to create adaptive variants of reinforcement learning, which will then be implemented in Virgo. This is a largely unexplored research frontier, on which we will invest a substantial part of the work planned for the project.

How can the project be useful for the Einstein Telescope?

The link with ET is very strong. As mentioned earlier, this type of noise becomes particularly significant at low frequencies, precisely one of the regimes in which the future experiment will operate. To minimize low-frequency noise and achieve the desired (and very ambitious) performance of the detector, it will be essential to implement several innovative technologies, including intelligent control based on artificial intelligence. Moreover, it is important to recall that the initial development of the adaptive algorithms will be carried out on Gemini, a test platform developed within the framework of the NRRP ETIC project, which supports the Italian candidacy to host ET.

How will you invest the funding?

Most of the funds will be invested in people. We want to build a strong group with specific expertise: we will hire a software engineer, several post-docs with experience in developing digital twins of detectors, as well as, of course, young PhD students. We will also invest in hardware and software instrumentation: in particular, we will acquire a GPU-based computer suitable for real-time control. All activities will be carried out in close collaboration with the Virgo collaboration, with a strong on-site presence.

(ms)

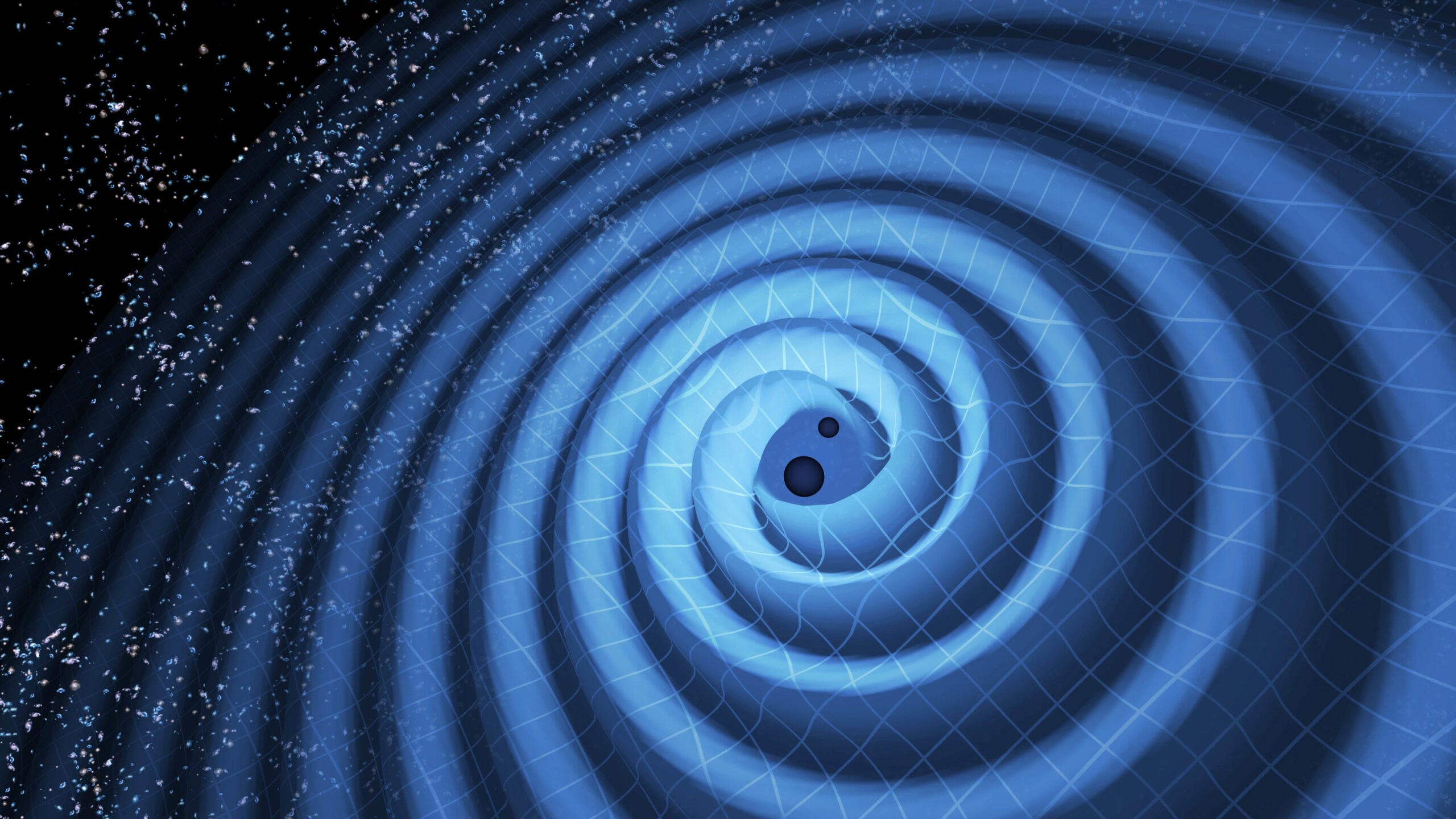

Featured image credit: LIGO/T. Pyle